Bienvenue chez moi. Lisez, regardez, et écrivez-moi! Amusez-vous! Welcome to my blog. Read, look, and write to me! Have fun!

Friday, June 29, 2007

Thursday, June 28, 2007

Sunday, June 24, 2007

Seattle 1959 & 1990

by TVB

June 2005

In 1990 I returned to see the neighborhood, school, and small rental house where I spent eight traumatic months of my second grade year in 1959-60, when my mother decided to join my father during his sabbatical at the University of Washington. The environment was not similar in any way to my Vancouver home in the same state. The culture clash and my parents’ own struggles to make the arrangement work were sources of conflict I could not sort out as a child. I merely lived it. For many years the memories of that brief period remained etched sharply in my mind. The narrow alleys, the city streets, and the injustices I had faced, replayed in surreal fantasies in my dreams.

In the 1990’s I began to feel the impact of these memories in a different way. Now I had my own daughter. I pondered the effect of adult decisions on childhood memories. I pondered the effect of childhood memories on the sculpture which eventually becomes adult, the human being, the spirit that continues on, past the events.

In discussions about this period with my parents, I sense an apologetic response. But I must protest this! In truth, I would not trade away one day of that dark winter in Seattle. These events helped shape who I am, how I think, how I feel, and how I respond to hardships. They made me a better, stronger person.

Originally I wrote this piece for my sister and my parents, who share these memories from different perspectives. I also wrote it for my daughter who is growing up in completely different world. But more than this, I wrote it for myself, so that I would always remember.

*********************************************************************************************************************

Seattle, 1959 and 1990

The sun shines bright and sharply this day in March, on the narrow street in Seattle where I spent less than a year of my life as a child. Somehow, the bright sharpness seems to accentuate the narrowness of the street, a narrowness I don’t remember. It emphasizes colors I don’t remember either. It seems to me that those Seattle days in 1959 were gray and overcast, dark like a black and white photograph.

The little house sits up and far back from the street like it did then. The retaining wall in front of the lawn is still there -- the height of it a source of frustration when my balsa wood airplane sailed over it and I had to climb down to retrieve it from the sidewalk below. The wall I sat on, fastening my roller skates’ metal clamps to my shoes and tightening them down with the metal key, before taking to the sidewalk with a rough and noisy clatter. There is a big tree nearly engulfing the house. Was that tree there, and was it big? I don’t remember it.

The house is now tan with dark brown trim around the windows. Bicycles are parked on the front porch. In 1959, it was white with red window trim. Two little girls ran up the front porch then, and ran laps around and around inside the house on the dark wood floor, through the kitchen, dining room, and living room. My favorite dress was a shiny brown rayon hand-me-down with a big lace-trimmed collar. I remember my mother ironing it as we ran round and round on the shiny dark wood floor. The dress was dark brown and the floor was dark brown and in the dimness, my sister and I ran circles around her. My mother didn’t like that dress at all. She preferred to dress me in shades of blue, to match my eyes.

My sister Jan and I spent many hours playing “school” with our old fashioned school desk in the damp darkness of the basement of this house. After hard and heavy rains the basement flooded. Sometimes the water was several inches deep. My mother made a footpath of bricks so she could walk to the washing machine. I remember sloshing my feet through the water under clothing hung to dry on lines above me. The thick wetness of the air was unforgettable: pungent, moldy and sweet.

It was in this house where my mother taught me how to line the big trash can with newspapers, overlapping and folding them securely so they completely covered the inside of the can and would not slip down inside. One of my responsibilities was to take out the kitchen garbage and empty the pail into the big metal can. Once the paper sack full of garbage was too wet and as I lifted it, the bottom broke out and scattered garbage all over the porch and steps: a simple lesson of life, frozen in time, in my memory -- a mistake I haven't repeated since. It was always dark, damp, and cold out there, maybe because it was winter, and maybe because our back porch was in the shadow of Gretchen’s house next door.

Gretchen was tall, and older than my sister and me. Once we had a carnival in her yard. It was my idea – all the neighborhood kids would come and pay a penny to ride on our homemade rides or play one of our homemade games. One of the rides was a big cardboard box – the kids would climb inside, and we would rock them back and forth. We planned and planned, and on the day of the carnival it threatened rain. Under dark skies and dark tall evergreens and the dark shadow of Gretchen’s huge house we set up the carnival anyway, but nobody came. I don’t remember playing with Gretchen very much. Her life seemed quiet and lonely to me. I don’t think she had any brothers or sisters.

It was during the school year around Thanksgiving time when we made the move to Seattle. Jan and I were taken on a tour of Bryant School, with our mother, one evening before we attended classes. We were shown our classrooms and introduced to our teachers. We walked down long empty corridors, dark, with polished brown linoleum floors. Student art work was taped in a long row along the hallway. The skin of all the children in the drawings was colored with orange crayon. In secret voices we giggled about the drawings when we got home, and puzzled over rows of children with orange skin.

The school building and school yard were completely different from Lieser School in Vancouver, a single story, open-armed elementary school typical of the 1950’s, with kindergarten at one end and sixth grade at the other, caressing a wide playground with grass and dirt, swing sets, jungle gyms, and climbing bars.

Bryant School was a tall brick city school, with stairs and dark hallways. The schoolyard was surrounded by chain link fence, completely paved. Metal and concrete. A line painted down the center of the playground divided the girls’ side from the boys’. On the first day of recess, I eagerly dashed across this line, attracted by a swing set on the other side, only to be stopped in my tracks by bossy kids who told me I couldn’t go across the line because that was the “boys’ side.” I thought they were joking at first. But they weren’t; it was true.

A second chain link fence bisected the yard across the yellow line, designating a small section for the first graders. Jan was in first grade and I was in second, so we weren’t permitted to play together at recess. I remember the two of us crouched on opposite sides of the fence trying to offer solace to each other through the chain links, in this strange world where girls couldn’t play with boys, and first-graders could play with second-graders.

The kids didn’t have orange skin. But they were required to use orange for skin color in their drawings. It was only one of many rigid rules.

At lunch time we all sat at long tables in the cafeteria, with our classes. I could see Jan in the cafeteria, but I couldn’t sit with her. We were subjected to the rule of cafeteria monitors, fifth and sixth graders, who hovered over us to make sure a single word didn’t issue forth from our lips. If one did, we got a demerit. If we got three demerits, we were forced to line up in a row by the windows, shamed in front of the whole school population, and not released to the playground for recess. I did not talk. I was terrified of these militaristic kids who ruled our lives at lunch time. I didn’t have any friends to talk to anyway. But one time I got three demerits. I had to stand in that line. I watched as each table was dismissed for recess, one by one. As I cried, I think something in side me hardened as I stood there. This foreign land was unforgiving and cruel.

I remember many of the children who shared that space in Seattle with me for such a short time. Jane Bus had straight blond hair, bluntly chopped at her shoulders. I thought she looked like the Jane in our “Sally, Dick, and Jane” books. She was late to school every day. She complained of headaches. Every day she missed arithmetic, which was always our first lesson. She was chastised in front of the class by our teacher, Miss Partington, for her habit of being tardy and was accused of doing so on purpose because she didn’t like arithmetic (I didn’t either). Jane Bus had a sister named Cynthia Bus, who was in Jan’s first grade class.

There was an orphanage near the school, and some of the orphans went to school with us. In my childish imagination, orphanages conjured up romantic and tragic images, colored with exotic hues of storybook adventures. This orphanage was surrounded by a high fence, and I don’t remember which of my classmates lived there.

New words entered our vocabulary the year we lived in Seattle. “daddy-o,” “cool,” and “neat,” were inspired by the 1950's counterculture beatniks. Mom teased me when I said something was “neat.” She’d say, “Oh, you mean it’s clean and orderly?”

One time words got me in trouble. We were having a spelling lesson, and Miss Partington asked for volunteers to write words on the blackboard that rhymed with "sell." This was easy! This was too easy! I could think of all of the ordinary words: tell, bell, spell. But I wanted to be different. I wanted to think of a word that no one else would think of. I thought of a word I believed meant to call out loudly, like "holler" or "yell." I eagerly raised my hand, and confidently approached the board. Proudly, in neat, straight letters, I wrote “h-e-l-l”. Silence. Gasp! “Um-m-m-m!” I could feel my face grow hot as the kids breathed the shameful admonition. I had no idea that I had written a bad word, but all the kids in this Catholic neighborhood sure knew it. I had mistakenly mixed the two words. My teacher was kind. "Now, class," she said. "Teresa didn't mean to write a bad word," and she told them that I didn’t know any better. I was surprised that she intervened on my behalf, and it offered me some small comfort whenever that embarrassing event replayed itself in my mind, as it often did for a long time afterward -- still carrying its emotional impact.

Miss Partington was somewhere near the age of a grandmother, with a matron’s stature, and gray hair, the image of a stereotypical “old maid schoolteacher.” Her absence of malice toward me was perceived by me as kindness. She called me Teresa, which is what I told her I wanted to be called, thinking it sounded more formal or glamorous. But it made me feel even more foreign and different. After that, I never asked anyone to call me Teresa again, and it still rubs me wrong when people do.

After school, Jan told me stories of how Miss Bouvier (or some such French name) would punish the first grade kids in her class by hitting them with a ruler, or drawing a small circle on the blackboard and forcing the child to stand against it with his nose in it. The ultimate disciplinary method was to lock the child in the closet. Dark as those days seemed to me, it was hard to believe that those punishments were still administered by public school teachers at the dawn of the 20th century's sixth decade! Did this really happen? It would have been easy to attribute the stories to the active imagination of a small girl. However, Jan insisted the stories were true, and my shy and introverted sister was not prone to lies. Probably because she was quiet and withdrawn, she never fell victim to her teacher’s insane aggression, merely because she wasn’t noticed.

I remember the winter evenings as cold and dark and long. I realize now that they really were longer and darker because of Seattle’s more northerly latitude. That year the Pacific Northwest was blanketed by snow. But it didn’t snow as much in Seattle as in Vancouver that winter, and I regretted that I couldn’t be back at my old home to play with my friends in the snow. The girls in my Blue Bird group sent me a big manila envelope stuffed with letters from all of them, telling me about the big snow. I missed them.

I fantasized a lot about moving back to Vancouver. I imagined myself returning to my class at Lieser School, and all my friends flocking around me, telling me how much they missed me, and how glad they were that I was back.

My mother found a job as an elementary school librarian in a suburban district far from our university neighborhood home. We had to drive on long freeways to get there. Sometimes on weekends I went with her when she had work to do. I always liked visiting the schools where my mother worked. It felt magical, silent without students, chairs empty, sometimes on tables. I liked playing on the rolling book carts and drawing on the blackboards. I liked the smell of chalk dust and crayons and books and floor wax. I liked to pull the 5th and 6th grade text books off the shelves. I was proud of my ability to read them. I remember the Shoreline school library as being light and lined with windows, with modern tables and chairs, so much different from the darkened halls and wooden furniture of Bryant School.

Because Mom and Dad didn’t get home until late, Jan and I needed a place to go after school. Near Bryant School there lived a family that would take us. I don’t know how much my parents paid them to baby-sit. The five kids went to Catholic school. I never got to know them, and I can’t even remember their names. Their father was a professional sign painter. Down in the basement we watched as he expertly and quickly painted the sale signs on big sheets of butcher paper, signs we would later see in the grocery store window.

We didn’t spend much time inside, however. Usually the street outside was full of kids riding bikes. Spring had come, and my mother had taken me to Sears and bought two new dresses for my birthday. I was wearing my favorite, the yellow one, for the very first time. I was devastated when I fell off my bike into the gravel, which tore little holes in the cotton skirt. I missed my mother, and my knee was bleeding, and my dress was ruined. I didn’t think there was any way to mend it. But later my mother soothed me, and solved the problem. She got some little daisy appliqués and sewed them over the holes. That made the dress even prettier than before!

Another day when we were playing in the street, a child ran up to the house in tears, announcing that one of the neighbor girls had been hit by a car. Her mother had sent her to get a pound of butter at the corner grocery store. A jolt of fear and alarm ran through me, and then unexplainable bleak sadness when the boy reported that the victim’s first words, as she lay injured in the street, were concern about the smashed butter.

One night my parents were to get home unusually late, and Jan and I had to stay at the Catholic family’s home for dinner. We had to sit quietly to eat alone in the kitchen, while the Catholic family sat together in the dining room. Through the door I caught a glimpse of them, sitting around a big table in warm golden light, as they went through their prayers, and crossed themselves. Unable to understand the gestures, I had awareness of their powerful significance. What was it that was so mysterious, and why could we not be a part of it? Once again, Jan and I were outsiders in a strange dark world.

As if there weren’t enough real mysteries in the strange activities of those around me, mysteries in the new rules I was expected to know and follow, my mind invented imaginary intrigues that played like fascinating stories in my mind. The city alleys fascinated me, and I imagined following them to strange and wonderful corners, where life would be magic. During this time when I craved my mother's reassurance and company, she was struggling with her own struggles of which I was unaware. We often argued, and I began to think of her as my secret enemy. Without a logical reason, I imagined she was plotting against me to hurt me. I was angry at her, and she was often angry at me.

However, one special evening with my mother shines like gold in my mind. She and I were home alone together, a rare occasion. "What shall we play?" she said. Then, "I have an idea!" She brought out some wooden blocks and a roll of tin foil. We built a castle out of the blocks and then we covered it with shiny silver foil. More than the details of the activity itself, the emotional imprint remains intense in my memory. It seems to me that we were fully immersed, and the wonder stays with me. I begged her to do it again, but, like true magic, it could not be called up on demand.

I am trying to remember my father in Seattle. I know he was there, but he’s missing from most of my memories of those days. I suppose he was spending most of his time studying at the University. What I do remember is the setting for our father/daughter conversations: me sitting on my top bunk, at eye-level with my six-foot-tall father. He told me about his studies, and said he was working on his thesis. "What's a thesis?" I asked. Oddly, an image of toilet paper comes to my mind! He told me that a thesis was a “long paper.”

It was also from the top bunk where I learned from my dad the trick for remembering how to add 9’s: to first add as if adding to 10, then subtract 1 – a simple trick which has helped me ever since. I remember another conversation that demonstrates the introspective and reflective quality of my father’s thinking. Evidently he had been reflecting on the experience of aging. He said that as a young man it never occurred to him that he would ever be thirty. He must have been thirty-three in 1959.

My top bunk bed had a wooden safety rail and I remember how it slipped in place across the mattress edge so that I wouldn’t roll off the precipice in the night. I still remember the smooth feel of the finish and the weight of it, and the sound as it slipped into the brackets that held it in place. It was removable, but it was a bit unweildy for a seven-year-old.

This didn’t stop me from removing it when we wanted to play “Peter Pan.”

More than anything I wished I could fly like Wendy in the Disney version of the movie. One night after dinner, Jan and I were playing “Peter Pan.” It was my bright idea to “fly” off the top bunk. I believed that if I just imagined hard enough, I would actually take flight. I perched on the edge of the high mattress, spread my arms, concentrated with the full force of my brain energy, and leaped. This would take practice! So I repeated the drill, over and over, certain that success would come. In my eagerness to take to the air, at one moment my foot slipped and I went down with a thud, belly-flopping on the hard wooden floor, chin extended. As the blood gushed from the tip of my chin, Dad and Mom rushed us off to the hospital emergency room in our pajamas. I still have the scar, a smiling crescent on my chin, revealing the seven stitches I received that night at the hospital.

We lived in Seattle no longer than eight months. Yet, I have more memories from this time than from any other time in my childhood, and the memories are rich and crisp. Those days were sad, lonely, and dark, and seemed an eternity to me as a seven-year-old.

After the school year ended, we returned to our house in Vancouver, and I started third grade at Lieser School. My friends did not flock around me and tell me how much they missed me. But life went on as before, sane and safe, and my same old friends were still my same old friends. No one could believe my fantastic stories of how, in Seattle, boys and girls were separated on the playground, and no one was allowed to talk at lunch time!

The 1990 spring sunshine at 5518 N.E. 26th Street seems to put my memories into perspective, shoves them back into the shadowy past. Still, the images remain in a spotlit corner of my life's stage, isolated in place, illuminated in sharp three-dimensional clarity.

I would not trade away a single experience of those painful months, even if I could. Some small things about my character would certainly be different had I never lived through those things. I was able to escape to what I perceived as a saner world, a world I understood. But now I wonder about those who couldn’t escape, and about those who found as much animosity at home as they did in the cold concrete world outside it. Do they remember too? Was their character enriched, damaged, or destroyed? Are their memories dark, like mine?

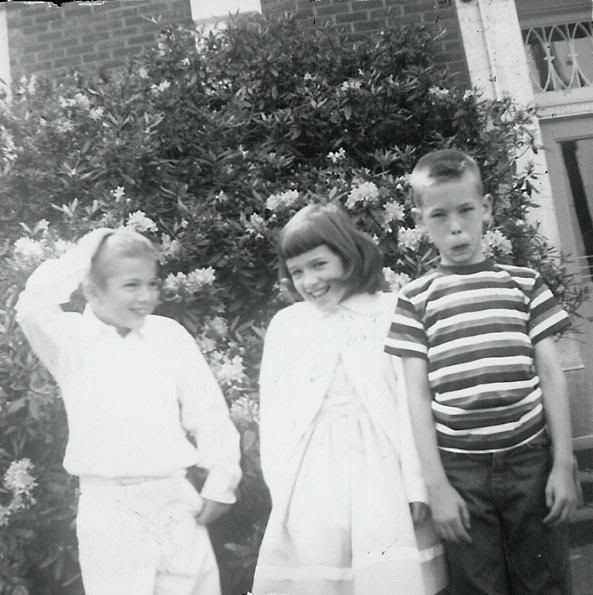

(Author's note: I took these photos of my classmates and my teacher, Miss Partington, with my Brownie camera on the last day of school. My sister, Jan, is shown in the photo below, front row, third from left.)

Il fait frais, le ciel est couvert et le matin est gris.

Je rêve à la mer Méditerranée et les couleurs d'été au sud de France. J'écoute la musique française. Je suis heureuse parce que j'ai trouvé la chanson "La Mer" (Charles Trenet) et je l'ai mise sur mon profil MySpace.

D'autre côté, je me sens productive. J'ai nettoyé le garage hier. Ce travail est satisfait. Qu'est-ce qu'on va faire aujourd'hui? Je ne sais pas. On va voir. Une chose est claire: je n'irai pas en France.

Saturday, June 23, 2007

Thursday, June 21, 2007

Sunday, June 3, 2007

How Elsie Finally Managed Her Neurosis and Learned to Love

Nearly midnight as I left my shift at Denny's and began to pull my car out of the parking lot, I saw a flicker of white and black fur reflected in the headlights. A tiny kitten flashed and was gone in an instant, swallowed by night-black bushes that lined the creek between the restaurant and the freeway. Carefully, quietly, I opened my car door, "Here kitty kitty!" But she didn't come out. Evidently this one was too wild and terrified, oblivious to the fact that I was probably the most ardent cat-lover in the whole world, and getting to know me would provide immediate relief from her hunger, cold, and anxiety! Sadly, I couldn't convince her, so I got back into my car and drove home, reflecting on the many cats that had been left to scratch out a living on the greasy pavement behind the restaurant. The pretty and friendly and lucky ones might find a home with a dishwasher or warm-hearted customer. But the scared and lonely and desperate ones usually met with a dismal end.

I didn't think about Elsie again for several months. When I saw her next, I recognized her immediately as the little kitten I had glimpsed earlier in the winter. She was bigger, but emaciated, and still had the same furtive feral movements. When I tried to approach her, she jolted and darted like a mouse in a kitchen. But she appeared briefly from time to time, at the edge of the parking lot, and I began putting cat food out for her. One day she decided to take it; she was starving.

I stayed distant, and watched motionless as she hungrily gobbled, casting cagey glances my way. She was full grown now, but she was small. Her coat was matted and filthy, the white under-fur stained with parking lot grease. Her backbone seemed malformed, unnaturally curved, probably from inadequate nutrition. I began calling her "L.C." for Little Cat, and her name became "Elsie."

If you want to get to know a cat, the first thing is to tune in and pay attention to what that particular cat is like. Cats are like people, and listening to a cat's spirit is like listening to a person's spirit. It is unique. Like people, cats have distinct needs, desires, neuroses, confusion, and wisdom. Elsie was neurotic to the point of dysfunction, obviously. That's what happens to cats and to people when they have been hurt, when they have carried too great a burden. They get stressed out.

So I listened to Elsie. Every day I put the food out behind the bushes at the edge of the parking lot. I stayed back and I waited. I stayed still. After awhile I tried moving a tiny bit closer. And I waited and stayed still and listened. By attuning to her I knew when it might be okay to try moving closer. Eventually I was right next to her. I didn't try to touch her, but stayed close each day, just waiting, watching, and listening to her spirit.

One day I reached out tenuously, and she let me stroke her fur and she purred as she ate. This hesitant truce defined our relationship for several weeks, but if anyone else approached us, she dashed away, her feral instinct taking over.

The rain was especially heavy that year, and Elsie's dirty coat was often soaked. Bill and Marie came to Denny's every day for coffee and pie. One day Bill brought Elsie a new home – a large milk crate covered with plastic sheeting. We put a towel-covered pillow inside and hid the box out of sight in the bushes. Now Elsie had a secret refuge from the wet rain.

But I was still the only person she allowed close to her. My goal was to earn enough of Elsie's trust to be able to take her home. I believed this would be a better life for her than the fringes of the restaurant parking lot. So one day I decided to try to pick her up. It was risky. She might panic, scratch, bite, and dart away, never again to trust me or any other human. But it was a risk I had to take if I were ever going to succeed in taking her home.

So, after she finished eating, and she was purring as I gently stroked her head and scratched her ears, I slowly lifted her to my chest. To my amazement, she nestled her head under my chin cuddling close, letting forth a soft throaty purr. I had earned her trust. This love-fest became a daily ritual. I decided it was time to take Elsie to her new home, my home, full of warmth, comfort, food, and soft catnap chairs. Finally Elsie would have a life of ease—something every cat deserves. I lifted her up and stroked her, and told her of the wonderful comforts in store for her. She also needed a bath, a health check, and she needed to be spayed. I didn't tell her about that part. I put her in the car and drove the short distance to my house. She wasn't happy, but she didn't complain either. She trusted me.

The first thing I needed to do was give her a bath. Although she had grown fat from nutritious food, her fur was still grimy and dingy, streaked with black grease. Again, I knew I was risking panic, attack, and loss of her trust, but she needed a bath and there was no getting around it. It's well-known that cats hate water, but contrary to common belief, it isn't difficult to bathe a cat. It may be unpleasant, but it isn't difficult.

I put a few inches of warm water into the sink, and readied myself. Plunging Elsie's body in, I held her firmly with one hand, and lathered her fur with the other. She howled as if I were burning her with hot pokers. What betrayal! I felt the shame of a hypocrite, and I begged her forgiveness.

It was over in five minutes. I bundled her in a towel and tried to dry her fur, but she got away from me. She slunk off under the antique sideboard where I couldn't reach her, and urgently and madly pulled at her wet fur with her sandpapery tongue. I was sure she was full of vengeful thoughts and would never forgive me.

A few hours later her fur was dry. She came out from under the furniture and she strutted toward me, a creature transformed! The gray dinginess was gone. Now the white of her fur was dazzling and the black was sleek and glossy. She was beautiful and she knew it. I marveled as she strutted around the room. Not only did she forgive me; she thanked me!

After that, her fur was never dingy again. She kept herself immaculately clean. It didn't take long to figure out that Elsie was not going to adapt to life in our home. She didn't take kindly to our other cats and retreated again to the hideaway under the sideboard. She refused to emerge. It was obvious that she was utterly unhappy.

Somewhat sadly I returned her to the restaurant parking lot. I had listened to her; I respected her wishes. Eventually we endured the ordeal of having her spayed, and she recovered well and then embarked on several years of routine and relationships, following the rituals in the Denny's parking lot to which she had become accustomed. The regulars paid her daily visits, each in his unique style.

John Estrada was Elsie's second favorite, after me. He was a widower in his 80's who lived alone, a small quiet man with a big heart. Every afternoon he came to the restaurant for coffee and company. His mammoth barge of a mid-70's American car had a trunk immense enough to carry a refrigerator. And he loved Elsie. He started bringing her food. Walking and bending were hard for him, so he opened his car trunk and set the bowl of cat food up inside. The trunk lid remained open while John went inside for coffee and conversation. To my amazement, Elsie didn't hesitate to jump up into the open trunk and munch down! Spring sunshine now warmed the parking lot, and sometimes she even curled up there for a sunny nap after filling her belly.

Elsie grew attached to John. She learned to recognize his car, and watched for it from her hiding place in the bushes. As he cruised into the lot, Elsie dashed to meet him, eagerly awaiting the open trunk and tasty treats inside. Eventually gentle John was able to coax her into his arms where he wooed her with gentle words and soft caresses. He and I were the only ones she ever permitted this intimacy.

A few years later, the time came for a life change. I was moving on; my husband and I were selling the restaurant after fifteen years. We were moving to Jackson Hole, Wyoming to pursue another chapter in our lives. What would become of Elsie? I had comprehended her misery when I tried to take her home with me. A forcible move from her familiar turf was not an option. But it worried me. A Denny's parking lot is a dangerous place for a cat; a 24-hour coffee shop attracts dumpers-of-cats and worse, a seedy array of the lowest humans who get twisted satisfaction from the torture of small animals and children. Elsie knew this on some level, of course — at least she knew from experience about the lowest element of earth's most highly evolved animal. But she couldn't understand that her choice of home had more of those creeps than other places. She figured her experience was Universal Truth and she had learned to manage life's dangers by carving out a small corner where she could be in control of its elements. This was how Elsie learned to deal with her neurosis and anxiety. What Elsie knew was that her Denny's parking lot also brought people who loved her. She had carefully and deliberately chosen the ones that she allowed into her life. It was all she needed. It was enough.

I knew that Elsie would miss me. But that sadness was preferable to unendurable anxiety of facing the unknown, the uncontrollable. Bill and Marie would continue their visits, and Elsie could rely on John to bring his car trunk and treats every day. So we went, and we left Elsie. Reports came to us that life continued as usual for Elsie and the others at Denny's.

Twenty years have now passed and Elsie is gone. So are John Estrada and Bill and Marie and the other kindhearted citizens who shared coffee and stories across the counter in that place on the sunny and rainy California Central Coast on Highway 101. But I see them still, in my mind and dreams. Elsie let me into her life, and I'll never forget her. Anyway, that's what it's all about – trust and risk – and figuring out how to manage a corner of this scary world.

I Am From

I am from stories and superstitions

Smorgasbords and potlucks

Vikings and Hillbillies

the Sea

and a valley filled with Water.

I am from drive-in theaters

Ballet class and Blue Birds

Climbing bars and easels

Cone-hat birthday parties

Sally, Dick, and Jane

and backyard dramas.

I am not from Barbie dolls my mother wouldn't buy.

I am from rain and green

Mud puddles, rubber boots

Pulled tight over saddle shoes

Barefoot soles blackened

by summer city pavement.

I am not from white go-go boots my mother wouldn’t buy.

I am from the Beatles

Joan Baez and Bob Dylan

Peace rallies, Earth Day

And we shall overcome.

I am not from The Lawrence Welk Show.

I am from divorce,

mended one year later.

I am from porcelain broken angel wings

Re-attached, just a trace of brown glue

Revealed in the crack.

I am from

a-house-should-look-lived-in

and no-singing-at-the-table.

I’m from "If you sing before breakfast

you’ll cry before nightfall."

I’m from the Carter Family

and the Man in Black.

I am from “Que Sera Sera.”

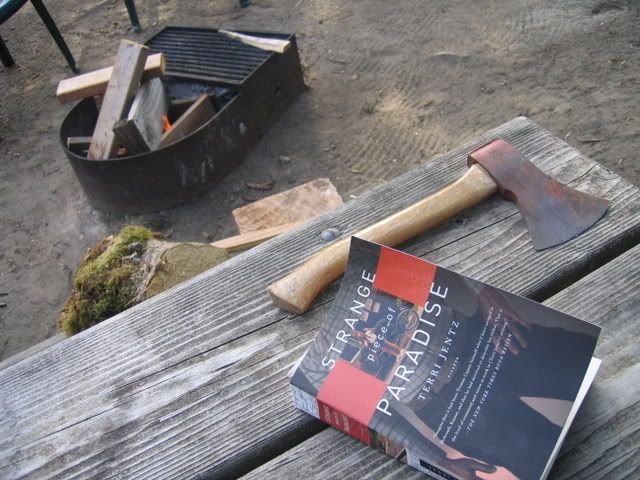

strange strange piece of paradise

This is one book I do NOT want to live in.

Camping in

Two weeks later, I was reading the final chapters. I sat in the hospital waiting room as my husband was having surgery on his shoulder. That's where I was, reading about the interviews with the nurses in the

The man next to me was telling me about his 20-year-old daughter. He had recently bought her a brand new car. She had been in an argument with her boyfriend. In a rage, the boyfriend had yanked back the door of the car and dented it. The man told me, "'I was so mad I wanted to take an ax to the roof of his car,' but she told me not to do that, because she said he would blame her." An ax! (I felt like I was living in the book.)

A local surgeon with one of the best reputations in town is named Dr. Hacker. While that would seem to be strange enough in its own right, on this particular occasion one of his patients got his name wrong, and mistakenly referred to him as "Dr. Hatchet." (I felt like I was living in the book.)

Terri Jentz writes about events converging in ways that seem to be metaphysical. On her first trip to

This type of experience has happened to me from time to time throughout my life. It's not only a sequence of events, but also a certain feeling that accompangies them. It really does feel like some force from the spiritual world is making itself visible through physicality, to put itself in my line of vision and to bring my attention to something important. Other times it's nothing important at all, but just seems to be there to entertain me.

When I was younger I paid little attention. Then there were times when, through negligence or power of will, I rejected the insights trying to make their way into my consciousness because I didn't like what they were telling me. Perhaps it didn't seem to match what I thought I wanted, or simply was not convenient. I went forcefully in the other direction. The result was always something I regretted -- sometimes even devastating, with consequences that could not be undone.

It's interesting that Terri Jentz relates that she had a premonition against stopping at

Does everyone have these sorts of metaphysical sensations? Is it the inexperience of youth that causes us to ignore them? Or is it the fault of our hyper-paced, competitive, aggressive, violent and self-serving culture, that rejects "intuition" as nonsense, even going so far as to call it "magical thinking" -- a symptom of mental illness -- causing us to question our deepest insights?

As I get older I give it more of my attention, and it does indeed entertain me, amuses me and makes me smile (driving through the historic neighborhood on my way to work, a circus-like melody playing on the CD, suddenly a unicyclist appears out of the foggy mist, pedaling across the road, crossing my path. Surreal.)