Seattle 1959 & 1990

by TVB

June 2005

In 1990 I returned to see the neighborhood, school, and small rental house where I spent eight traumatic months of my second grade year in 1959-60, when my mother decided to join my father during his sabbatical at the University of Washington. The environment was not similar in any way to my Vancouver home in the same state. The culture clash and my parents’ own struggles to make the arrangement work were sources of conflict I could not sort out as a child. I merely lived it. For many years the memories of that brief period remained etched sharply in my mind. The narrow alleys, the city streets, and the injustices I had faced, replayed in surreal fantasies in my dreams.

In the 1990’s I began to feel the impact of these memories in a different way. Now I had my own daughter. I pondered the effect of adult decisions on childhood memories. I pondered the effect of childhood memories on the sculpture which eventually becomes adult, the human being, the spirit that continues on, past the events.

In discussions about this period with my parents, I sense an apologetic response. But I must protest this! In truth, I would not trade away one day of that dark winter in Seattle. These events helped shape who I am, how I think, how I feel, and how I respond to hardships. They made me a better, stronger person.

Originally I wrote this piece for my sister and my parents, who share these memories from different perspectives. I also wrote it for my daughter who is growing up in completely different world. But more than this, I wrote it for myself, so that I would always remember.

*********************************************************************************************************************

Seattle, 1959 and 1990

The sun shines bright and sharply this day in March, on the narrow street in Seattle where I spent less than a year of my life as a child. Somehow, the bright sharpness seems to accentuate the narrowness of the street, a narrowness I don’t remember. It emphasizes colors I don’t remember either. It seems to me that those Seattle days in 1959 were gray and overcast, dark like a black and white photograph.

The little house sits up and far back from the street like it did then. The retaining wall in front of the lawn is still there -- the height of it a source of frustration when my balsa wood airplane sailed over it and I had to climb down to retrieve it from the sidewalk below. The wall I sat on, fastening my roller skates’ metal clamps to my shoes and tightening them down with the metal key, before taking to the sidewalk with a rough and noisy clatter. There is a big tree nearly engulfing the house. Was that tree there, and was it big? I don’t remember it.

The house is now tan with dark brown trim around the windows. Bicycles are parked on the front porch. In 1959, it was white with red window trim. Two little girls ran up the front porch then, and ran laps around and around inside the house on the dark wood floor, through the kitchen, dining room, and living room. My favorite dress was a shiny brown rayon hand-me-down with a big lace-trimmed collar. I remember my mother ironing it as we ran round and round on the shiny dark wood floor. The dress was dark brown and the floor was dark brown and in the dimness, my sister and I ran circles around her. My mother didn’t like that dress at all. She preferred to dress me in shades of blue, to match my eyes.

My sister Jan and I spent many hours playing “school” with our old fashioned school desk in the damp darkness of the basement of this house. After hard and heavy rains the basement flooded. Sometimes the water was several inches deep. My mother made a footpath of bricks so she could walk to the washing machine. I remember sloshing my feet through the water under clothing hung to dry on lines above me. The thick wetness of the air was unforgettable: pungent, moldy and sweet.

It was in this house where my mother taught me how to line the big trash can with newspapers, overlapping and folding them securely so they completely covered the inside of the can and would not slip down inside. One of my responsibilities was to take out the kitchen garbage and empty the pail into the big metal can. Once the paper sack full of garbage was too wet and as I lifted it, the bottom broke out and scattered garbage all over the porch and steps: a simple lesson of life, frozen in time, in my memory -- a mistake I haven't repeated since. It was always dark, damp, and cold out there, maybe because it was winter, and maybe because our back porch was in the shadow of Gretchen’s house next door.

Gretchen was tall, and older than my sister and me. Once we had a carnival in her yard. It was my idea – all the neighborhood kids would come and pay a penny to ride on our homemade rides or play one of our homemade games. One of the rides was a big cardboard box – the kids would climb inside, and we would rock them back and forth. We planned and planned, and on the day of the carnival it threatened rain. Under dark skies and dark tall evergreens and the dark shadow of Gretchen’s huge house we set up the carnival anyway, but nobody came. I don’t remember playing with Gretchen very much. Her life seemed quiet and lonely to me. I don’t think she had any brothers or sisters.

It was during the school year around Thanksgiving time when we made the move to Seattle. Jan and I were taken on a tour of Bryant School, with our mother, one evening before we attended classes. We were shown our classrooms and introduced to our teachers. We walked down long empty corridors, dark, with polished brown linoleum floors. Student art work was taped in a long row along the hallway. The skin of all the children in the drawings was colored with orange crayon. In secret voices we giggled about the drawings when we got home, and puzzled over rows of children with orange skin.

The school building and school yard were completely different from Lieser School in Vancouver, a single story, open-armed elementary school typical of the 1950’s, with kindergarten at one end and sixth grade at the other, caressing a wide playground with grass and dirt, swing sets, jungle gyms, and climbing bars.

Bryant School was a tall brick city school, with stairs and dark hallways. The schoolyard was surrounded by chain link fence, completely paved. Metal and concrete. A line painted down the center of the playground divided the girls’ side from the boys’. On the first day of recess, I eagerly dashed across this line, attracted by a swing set on the other side, only to be stopped in my tracks by bossy kids who told me I couldn’t go across the line because that was the “boys’ side.” I thought they were joking at first. But they weren’t; it was true.

A second chain link fence bisected the yard across the yellow line, designating a small section for the first graders. Jan was in first grade and I was in second, so we weren’t permitted to play together at recess. I remember the two of us crouched on opposite sides of the fence trying to offer solace to each other through the chain links, in this strange world where girls couldn’t play with boys, and first-graders could play with second-graders.

The kids didn’t have orange skin. But they were required to use orange for skin color in their drawings. It was only one of many rigid rules.

At lunch time we all sat at long tables in the cafeteria, with our classes. I could see Jan in the cafeteria, but I couldn’t sit with her. We were subjected to the rule of cafeteria monitors, fifth and sixth graders, who hovered over us to make sure a single word didn’t issue forth from our lips. If one did, we got a demerit. If we got three demerits, we were forced to line up in a row by the windows, shamed in front of the whole school population, and not released to the playground for recess. I did not talk. I was terrified of these militaristic kids who ruled our lives at lunch time. I didn’t have any friends to talk to anyway. But one time I got three demerits. I had to stand in that line. I watched as each table was dismissed for recess, one by one. As I cried, I think something in side me hardened as I stood there. This foreign land was unforgiving and cruel.

I remember many of the children who shared that space in Seattle with me for such a short time. Jane Bus had straight blond hair, bluntly chopped at her shoulders. I thought she looked like the Jane in our “Sally, Dick, and Jane” books. She was late to school every day. She complained of headaches. Every day she missed arithmetic, which was always our first lesson. She was chastised in front of the class by our teacher, Miss Partington, for her habit of being tardy and was accused of doing so on purpose because she didn’t like arithmetic (I didn’t either). Jane Bus had a sister named Cynthia Bus, who was in Jan’s first grade class.

There was an orphanage near the school, and some of the orphans went to school with us. In my childish imagination, orphanages conjured up romantic and tragic images, colored with exotic hues of storybook adventures. This orphanage was surrounded by a high fence, and I don’t remember which of my classmates lived there.

New words entered our vocabulary the year we lived in Seattle. “daddy-o,” “cool,” and “neat,” were inspired by the 1950's counterculture beatniks. Mom teased me when I said something was “neat.” She’d say, “Oh, you mean it’s clean and orderly?”

One time words got me in trouble. We were having a spelling lesson, and Miss Partington asked for volunteers to write words on the blackboard that rhymed with "sell." This was easy! This was too easy! I could think of all of the ordinary words: tell, bell, spell. But I wanted to be different. I wanted to think of a word that no one else would think of. I thought of a word I believed meant to call out loudly, like "holler" or "yell." I eagerly raised my hand, and confidently approached the board. Proudly, in neat, straight letters, I wrote “h-e-l-l”. Silence. Gasp! “Um-m-m-m!” I could feel my face grow hot as the kids breathed the shameful admonition. I had no idea that I had written a bad word, but all the kids in this Catholic neighborhood sure knew it. I had mistakenly mixed the two words. My teacher was kind. "Now, class," she said. "Teresa didn't mean to write a bad word," and she told them that I didn’t know any better. I was surprised that she intervened on my behalf, and it offered me some small comfort whenever that embarrassing event replayed itself in my mind, as it often did for a long time afterward -- still carrying its emotional impact.

Miss Partington was somewhere near the age of a grandmother, with a matron’s stature, and gray hair, the image of a stereotypical “old maid schoolteacher.” Her absence of malice toward me was perceived by me as kindness. She called me Teresa, which is what I told her I wanted to be called, thinking it sounded more formal or glamorous. But it made me feel even more foreign and different. After that, I never asked anyone to call me Teresa again, and it still rubs me wrong when people do.

After school, Jan told me stories of how Miss Bouvier (or some such French name) would punish the first grade kids in her class by hitting them with a ruler, or drawing a small circle on the blackboard and forcing the child to stand against it with his nose in it. The ultimate disciplinary method was to lock the child in the closet. Dark as those days seemed to me, it was hard to believe that those punishments were still administered by public school teachers at the dawn of the 20th century's sixth decade! Did this really happen? It would have been easy to attribute the stories to the active imagination of a small girl. However, Jan insisted the stories were true, and my shy and introverted sister was not prone to lies. Probably because she was quiet and withdrawn, she never fell victim to her teacher’s insane aggression, merely because she wasn’t noticed.

I remember the winter evenings as cold and dark and long. I realize now that they really were longer and darker because of Seattle’s more northerly latitude. That year the Pacific Northwest was blanketed by snow. But it didn’t snow as much in Seattle as in Vancouver that winter, and I regretted that I couldn’t be back at my old home to play with my friends in the snow. The girls in my Blue Bird group sent me a big manila envelope stuffed with letters from all of them, telling me about the big snow. I missed them.

I fantasized a lot about moving back to Vancouver. I imagined myself returning to my class at Lieser School, and all my friends flocking around me, telling me how much they missed me, and how glad they were that I was back.

My mother found a job as an elementary school librarian in a suburban district far from our university neighborhood home. We had to drive on long freeways to get there. Sometimes on weekends I went with her when she had work to do. I always liked visiting the schools where my mother worked. It felt magical, silent without students, chairs empty, sometimes on tables. I liked playing on the rolling book carts and drawing on the blackboards. I liked the smell of chalk dust and crayons and books and floor wax. I liked to pull the 5th and 6th grade text books off the shelves. I was proud of my ability to read them. I remember the Shoreline school library as being light and lined with windows, with modern tables and chairs, so much different from the darkened halls and wooden furniture of Bryant School.

Because Mom and Dad didn’t get home until late, Jan and I needed a place to go after school. Near Bryant School there lived a family that would take us. I don’t know how much my parents paid them to baby-sit. The five kids went to Catholic school. I never got to know them, and I can’t even remember their names. Their father was a professional sign painter. Down in the basement we watched as he expertly and quickly painted the sale signs on big sheets of butcher paper, signs we would later see in the grocery store window.

We didn’t spend much time inside, however. Usually the street outside was full of kids riding bikes. Spring had come, and my mother had taken me to Sears and bought two new dresses for my birthday. I was wearing my favorite, the yellow one, for the very first time. I was devastated when I fell off my bike into the gravel, which tore little holes in the cotton skirt. I missed my mother, and my knee was bleeding, and my dress was ruined. I didn’t think there was any way to mend it. But later my mother soothed me, and solved the problem. She got some little daisy appliqués and sewed them over the holes. That made the dress even prettier than before!

Another day when we were playing in the street, a child ran up to the house in tears, announcing that one of the neighbor girls had been hit by a car. Her mother had sent her to get a pound of butter at the corner grocery store. A jolt of fear and alarm ran through me, and then unexplainable bleak sadness when the boy reported that the victim’s first words, as she lay injured in the street, were concern about the smashed butter.

One night my parents were to get home unusually late, and Jan and I had to stay at the Catholic family’s home for dinner. We had to sit quietly to eat alone in the kitchen, while the Catholic family sat together in the dining room. Through the door I caught a glimpse of them, sitting around a big table in warm golden light, as they went through their prayers, and crossed themselves. Unable to understand the gestures, I had awareness of their powerful significance. What was it that was so mysterious, and why could we not be a part of it? Once again, Jan and I were outsiders in a strange dark world.

As if there weren’t enough real mysteries in the strange activities of those around me, mysteries in the new rules I was expected to know and follow, my mind invented imaginary intrigues that played like fascinating stories in my mind. The city alleys fascinated me, and I imagined following them to strange and wonderful corners, where life would be magic. During this time when I craved my mother's reassurance and company, she was struggling with her own struggles of which I was unaware. We often argued, and I began to think of her as my secret enemy. Without a logical reason, I imagined she was plotting against me to hurt me. I was angry at her, and she was often angry at me.

However, one special evening with my mother shines like gold in my mind. She and I were home alone together, a rare occasion. "What shall we play?" she said. Then, "I have an idea!" She brought out some wooden blocks and a roll of tin foil. We built a castle out of the blocks and then we covered it with shiny silver foil. More than the details of the activity itself, the emotional imprint remains intense in my memory. It seems to me that we were fully immersed, and the wonder stays with me. I begged her to do it again, but, like true magic, it could not be called up on demand.

I am trying to remember my father in Seattle. I know he was there, but he’s missing from most of my memories of those days. I suppose he was spending most of his time studying at the University. What I do remember is the setting for our father/daughter conversations: me sitting on my top bunk, at eye-level with my six-foot-tall father. He told me about his studies, and said he was working on his thesis. "What's a thesis?" I asked. Oddly, an image of toilet paper comes to my mind! He told me that a thesis was a “long paper.”

It was also from the top bunk where I learned from my dad the trick for remembering how to add 9’s: to first add as if adding to 10, then subtract 1 – a simple trick which has helped me ever since. I remember another conversation that demonstrates the introspective and reflective quality of my father’s thinking. Evidently he had been reflecting on the experience of aging. He said that as a young man it never occurred to him that he would ever be thirty. He must have been thirty-three in 1959.

My top bunk bed had a wooden safety rail and I remember how it slipped in place across the mattress edge so that I wouldn’t roll off the precipice in the night. I still remember the smooth feel of the finish and the weight of it, and the sound as it slipped into the brackets that held it in place. It was removable, but it was a bit unweildy for a seven-year-old.

This didn’t stop me from removing it when we wanted to play “Peter Pan.”

More than anything I wished I could fly like Wendy in the Disney version of the movie. One night after dinner, Jan and I were playing “Peter Pan.” It was my bright idea to “fly” off the top bunk. I believed that if I just imagined hard enough, I would actually take flight. I perched on the edge of the high mattress, spread my arms, concentrated with the full force of my brain energy, and leaped. This would take practice! So I repeated the drill, over and over, certain that success would come. In my eagerness to take to the air, at one moment my foot slipped and I went down with a thud, belly-flopping on the hard wooden floor, chin extended. As the blood gushed from the tip of my chin, Dad and Mom rushed us off to the hospital emergency room in our pajamas. I still have the scar, a smiling crescent on my chin, revealing the seven stitches I received that night at the hospital.

We lived in Seattle no longer than eight months. Yet, I have more memories from this time than from any other time in my childhood, and the memories are rich and crisp. Those days were sad, lonely, and dark, and seemed an eternity to me as a seven-year-old.

After the school year ended, we returned to our house in Vancouver, and I started third grade at Lieser School. My friends did not flock around me and tell me how much they missed me. But life went on as before, sane and safe, and my same old friends were still my same old friends. No one could believe my fantastic stories of how, in Seattle, boys and girls were separated on the playground, and no one was allowed to talk at lunch time!

The 1990 spring sunshine at 5518 N.E. 26th Street seems to put my memories into perspective, shoves them back into the shadowy past. Still, the images remain in a spotlit corner of my life's stage, isolated in place, illuminated in sharp three-dimensional clarity.

I would not trade away a single experience of those painful months, even if I could. Some small things about my character would certainly be different had I never lived through those things. I was able to escape to what I perceived as a saner world, a world I understood. But now I wonder about those who couldn’t escape, and about those who found as much animosity at home as they did in the cold concrete world outside it. Do they remember too? Was their character enriched, damaged, or destroyed? Are their memories dark, like mine?

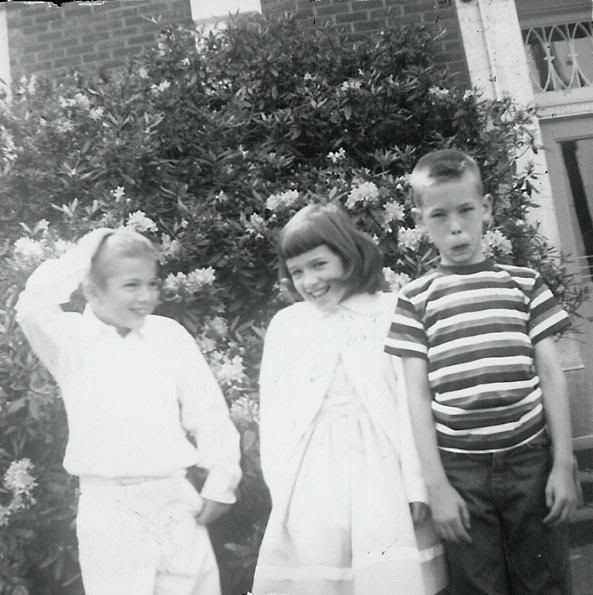

(Author's note: I took these photos of my classmates and my teacher, Miss Partington, with my Brownie camera on the last day of school. My sister, Jan, is shown in the photo below, front row, third from left.)

No comments:

Post a Comment